vs.

The Mayans were wrong, the holiday season has ended, New Year’s has come and gone, and we’re all settling in to 2013. It may be a new year, but it’s the same old problems for the future of journalism…or is it? Below, five of the most interesting nuggets I read this week about the state of print media, advertising and marketing.

1.

Andrew Sullivan, late of the Daily Beast, announced in a post called “New Year, New Dish, New Media” that he’s taking his site to the people. He’s leaving the advertiser-based media world entirely, as well as the venture-backed one:

We want to help build a new media environment that is not solely about advertising or profit above everything, but that is dedicated first to content and quality.

We want to create a place where readers — and readers alone — sustain the site. No bigger media companies will be subsidizing us; no venture capital will be sought to cushion our transition (unless my savings count as venture capital); and, most critically, no advertising will be getting in the way…. Hence the purest, simplest model for online journalism: you, us, and a meter. Period. No corporate ownership, no advertising demands, no pressure for pageviews.

2.

From an essay in yesterday’s NYT magazine called “Can Social Media Sell Soap?” by Stephen Baker on the value, or perceived value, of data- and social media-based marketing and advertising on social media today compared to the so-called heyday of advertising that’s depicted on Mad Men.

In the “Mad Men” depiction of an advertising firm in the ’60s, the big stars don’t sweat the numbers. They’re gut followers. Don Draper pours himself a finger or two of rye and flops on a couch in his corner office. He thinks…. Fellow humanists dominate Don Draper’s rarefied world, while the numbers people, two or three of them crammed into dingier offices, pore over Nielsen reports and audience profiles.

In the last decade however, those numbers people have rocketed to the top. They build and operate the search engines. They’re flexing their quantitative muscles at agencies and starting new ones. And the rise of social networks, which stream a global gabfest into their servers, catapults these quants ever higher. Their most powerful pitches aren’t ideas but rather algorithms. This sends many of today’s Don Drapers into early retirement.

While the rise of search battered the humanists, it also laid a trap that the quants are falling into now. It led to the belief that with enough data, all of advertising could turn into quantifiable science. This came with a punishing downside. It banished faith from the advertising equation. For generations, Mad Men had thrived on widespread trust that their jingles and slogans altered consumers’ behavior. Thankfully for them, there was little data to prove them wrong. But in an industry run remorselessly by numbers, the expectations have flipped. Advertising companies now face pressure to deliver statistical evidence of their success. When they come up short, offering anecdotes in place of numbers, the markets punish them. Faith has given way to doubt.

This leads to exasperation, because in a server farm packed with social data, it’s hard to know what to count. What’s the value of a Facebook “like” or a Twitter follower? What do you measure to find out?

3.

From a news item today titled “Two Custom-Publishing Powerhouses Join Forces,” by Stuart Elliott:

“We see a real shift going on from traditional advertising to a content-driven strategy,” Dan Kortick, managing partner at Wicks, said in a phone interview on Friday. “It’s more about engagement than exposure,” Mr. Kortick said, as content marketing offers “real engagement with your customer base.”

4.

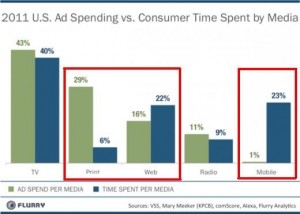

Derek Thompson of The Atlantic weighs in on why web advertising sucks and which of the models described in the quotes above will work going forward (spoiler alert: it’s probably a combination of both, depending on the scale and the goal).

It’s commonly understood that Web advertising stinks, quarantined as it is in miserable banners and squares around article pages. BuzzFeed’s approach is different: It designs ads for companies that aim to be as funny and sharable as their other stories. Jonah Peretti, the CEO of BuzzFeed, told the Guardian’s Heidi Moore that he attributed nearly all the company’s revenues to this sort of “social” advertising. “We work with brands to help them speak the language of the web,” Peretti said. “I think there’s an opportunity to create a golden age of advertising, like another Mad Men age of advertising, where people are really creative and take it seriously.”

The online reaction to the Dish [striking out on its own, without advertising] and BuzzFeed [getting $20 million in funding] seems to be that what Andrew’s doing is sort of quaint and old-fashioned and what BuzzFeed is doing is weird and revolutionary. The opposite is true. Funding a journalistic enterprise without advertising is weird and revolutionary and experimenting with ads that are suitable to their medium is a clear echo of history. Just as the first radio ads were essentially newspaper ads read aloud, and the first television ads were little more than radio spots over static images, many on the Web are fighting the last war rather than building ads that work for the Internet, journalism history professor Michael Schudson explained to me.

Banners and pop-up ads are so awful they practically sulk in their acknowledged awfulness, fully aware that they are interruptions rather than attempts to compete with editorial content for the readers’ attention. BuzzFeed (and other companies experimenting with designing advertising for their advertisers) gets that and tries to fix it. Just as TV ads are successful precisely because they try to be as evocative, funny, arresting, and memorable as actual TV, there’s no reason why advertising content shouldn’t aim to be as informative or delightful as an original online piece.

Even as Sullivan’s Dish is pushing the boundaries of subscriptions, testing how much a dedicated audience is willing to pay for online journalism that is supposedly free, BuzzFeed is pushing the boundaries of advertorial — advertising content like looks like editorial content — testing how far each side of their two-sided market (readers and companies) is willing to go. The future of paid journalism — if we can even try to guess at it — will probably be a blend of the two strategies celebrated this week: Ads that are less useless and ignorable, and readers who are asked to show a little more love than they’re used to.

5.

Finally, let’s wrap up with yet another pollyanna-ish piece from David Carr, titled “Old Media’s Stalwarts Persevered in 2012.” He has postulated that “old media,” by which he means broadcast networks, are “raining green” because they’ve learned from happened to music and print.

The worries about insurgent threats [to broadcasters] from tech-oriented players like Netflix, Amazon and Apple turned out to be overstated. Those digital enterprises were supposed to be trouncing media companies; not only is that not happening, but they are writing checks to buy content…. “As it turns out, the traditional television business is far stickier than people thought, and audience behavior is not changing as rapidly as people thought it might,” said Richard Greenfield, an analyst at BTIG Research.

Perhaps the numbers support this for now — this quarter, this year — but I think that’s a temporary glitch of the awful economy, not a harbinger of the future. As Carr reports, these giant corporations, instead of spending money, paid out dividends and financed stock buybacks. So sure, the numbers are up…but stuffing your savings under the mattress is not a long-term strategy. And its certainly not one that will not work for all “old media,” which Carr eventually acknowledges:

Another thing about those dinosaurs is that they aren’t really old media in the sense of, um, newspapers. When their content is digitized, it is generally monetized, not aggregated.

I’ll ignore the irony of having aggregated the thoughts above. And I won’t even comment on five white guys having written them in the first place, and the stories themselves being about other white guys, and what these facts say about the future (or is it past?) of media and advertising. Happy 2013.